Chicago Review, the Beats, and Big Table: 60 Years On

Cover of Big Table 1, 1959.

Preface

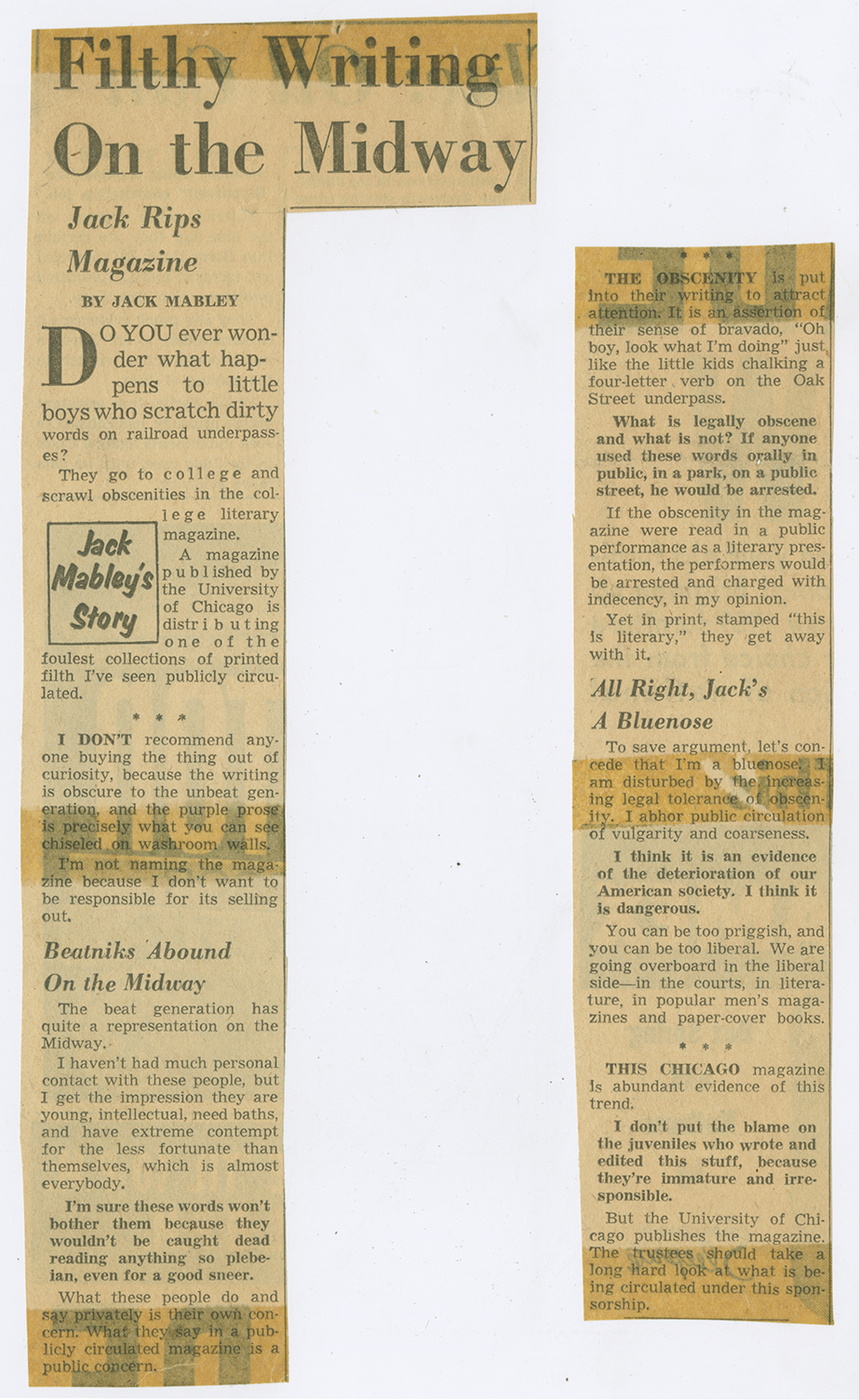

This year marks sixty years since the publication of the first issue of Big Table, the journal started by Irving Rosenthal, Paul Carroll, and other staff members of Chicago Review after the University of Chicago suppressed the Winter 1959 issue of CR. We gather a wide array of materials here to commemorate the anniversary, and to look back to an important episode in American literary history. The Big Table story, and CR’s history leading up to it, is told in detail in former Editor Eirik Steinhoff’s essay “The Making of Chicago Review: The Meteoric Years (1946–1958)“; this was published in CR’s sixtieth anniversary issue, and appears in an expanded, revised form here in this feature. Rosenthal and Carroll began publishing the Beats in 1958; some of the correspondence between the editors and Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and William S. Burroughs is included in this feature. Excerpts from Burroughs’s Naked Lunch appeared in two issues in 1958 (12.1 and 12.3); a journalist for the Chicago Daily News responded with an article titled “Filthy Writing on the Midway,” in which he called on the trustees, no less, of the university to “take a long hard look at what is being circulated” under their sponsorship.

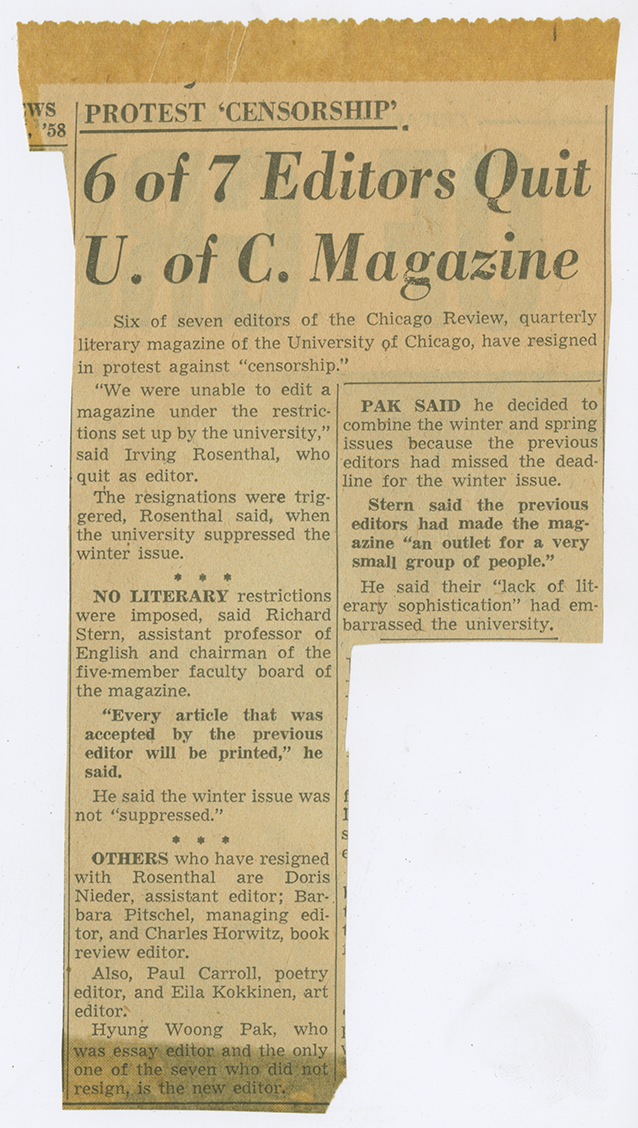

They did so, and soon Rosenthal was told by the Dean of the Humanities Division that the next issue had to be “completely innocuous.” Rosenthal called a staff meeting, the notes from which are included in this feature, in which two options were considered: refusing to comply with the strictures, or electing “a new editor of the Review who could publish in good conscience a next issue which would be acceptable to the University.” Understanding the risk that was posed to the future existence of CR in pursuing the first option, the second route was chosen by vote. Hyung Woong Pak was elected the new editor, and went on to edit several excellent issues. The rest of the editors resigned, taking with them the manuscripts of work by Burroughs, Kerouac, and Edward Dahlberg that were to appear in the next issue of CR, with which they started Big Table.

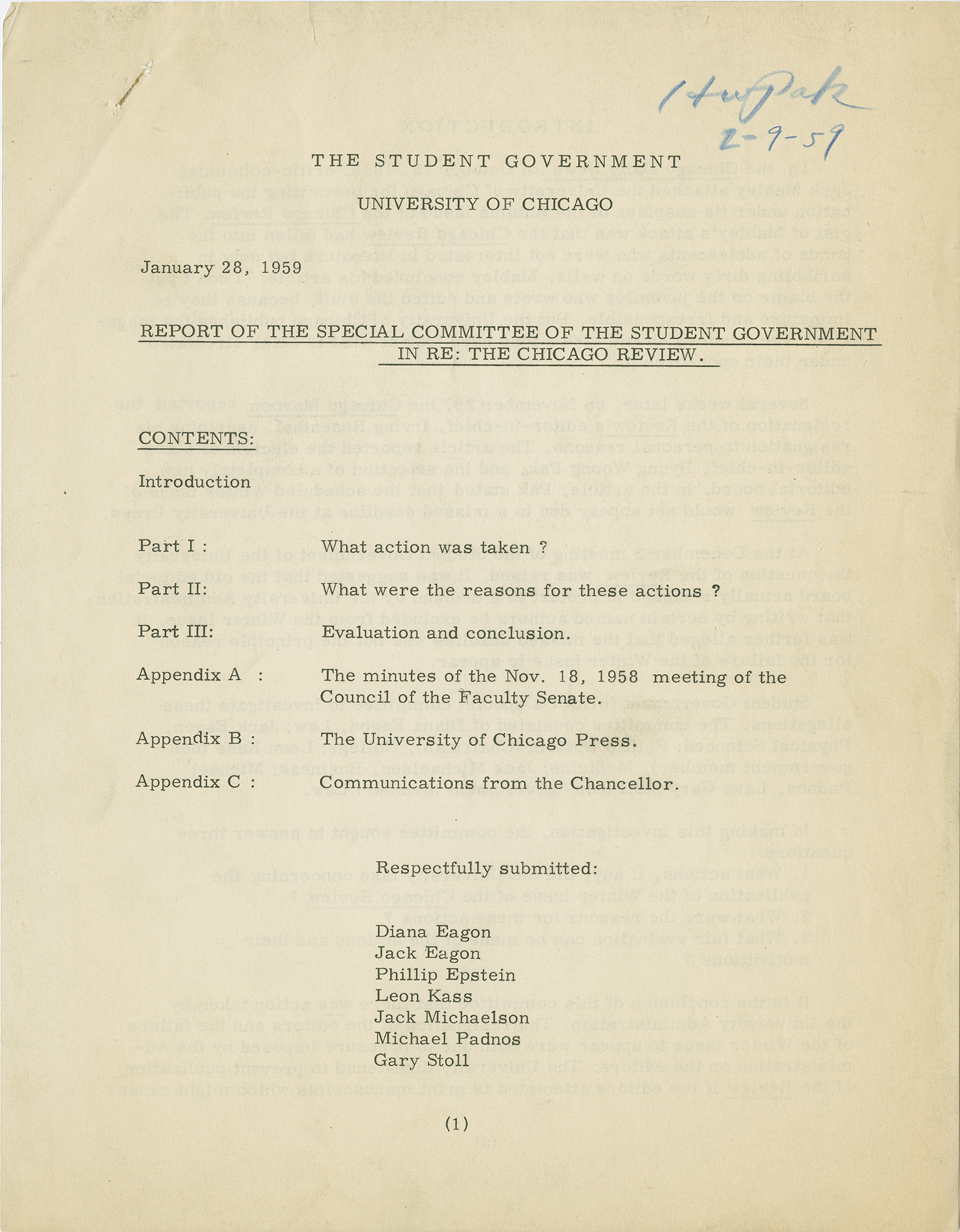

It was a principled editorial stand against censorship, and a shameful episode in the history of the administration of the University of Chicago, which has now made a brand out of championing “free expression.” The affair sparked off internal controversy, including an investigation by a Special Committee of the Student Government (selections of the report are included here), and the Chicago Maroon, the University’s student newspaper, covered the matter in detail. But it also became a matter of national debate—a number of clippings are included below—and was a part of a larger process of the triumph of Beat literature over what were perhaps the last attempts to suppress literary work in the US through the charge of “obscenity.” After suppression by the University, Big Table was confiscated by the US Post Office. The ACLU took up the case for the publication and won, Joel J. Sprayregen, counsel for the ACLU, claiming that “this is one of the most important censorship decisions” since James Joyce’s Ulysses.

Allen Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky, and Gregory Corso gave a poetry reading in Chicago as a fundraiser to help establish Big Table (the press release is included here). A snide article covered the event in Time magazine: “With the crashing madness of a Marx Brothers scene run in reverse, the Beatniks read their poetry, made their pitch for money for a new Beatnik magazine, The Big Table, and then stalked out.” This chauvinism from the literary establishment elicited a classic Beat response from the poets:

Your account of our incarnation in Chicago was cheap kicks for you who have sold your pens for Money and have no Fate left but idiot mockery of the Muse that must work in poverty in an America already doomed by materialism. You suppressed knowledge that the Chicago Review’s winter issue was censored by the University of Chicago; that the editors had resigned to publish the material under the name Big Table; that we offered our bodies and Poetry to raise money to help publish the magazine, and left Chicago in the penury in which we had come. […] You are an instrument of the Devil and crucify America with your lies; you are the war-creating Whore of Babylon and would be damned were you not mercifully destined to be swallowed by Oblivion with all created things.

The first issue of Big Table was a success, and Paul Carroll would go on to edit four more numbers, and publish several books under the imprint of Big Table Books. Rosenthal took the opportunity of the publication to tell his version of the story in an “Editorial,” which we include here. Not mincing words, Rosenthal refers to the administration’s actions as blatant censorship, writing that Lawrence Kimpton, the Chancellor at the time, “does not want free expression at the University of Chicago; he wants money.”

The episode left its mark on former editors, and has been passed down as a defining moment in the history of CR. As we approach the journal’s seventy-fifth anniversary in 2021, we’ve been collecting memoirs from former editors and staff members in an experiment in collective self-memorialization and self-historicization. To round out the feature, three memoirs are published here: one from Barbara Goldowsky, née Pitschel, who joined the staff under Rosenthal, resigning as Managing Editor; one from Edward Morin, who joined the staff at the same time as Rosenthal, and went on to serve in several editorial positions, moving on just before the Big Table fracas; and one from former Editor Peter Michelson, who joined the staff under Pak’s editorship just after the events of 1959. Together, the three memoirs recount the period leading up to the suppression ordeal, the event itself, and the aftermath.

Happily, the period of University oversight of CR passed, as did the period of attempts to suppress the Beats and other writers for obscenity. What has lived on is the writing itself, a testament, among other things, to editorial insight and courage.

– The Editors

§

The Making of Chicago Review: The Meteoric Years (1946–1958)

Like any literary periodical, Chicago Review has time woven into its fabric. The word “journal”—with jour, the French word for “day,” at its root—suggests an urgent, deciduous quality: a journal is a transitional document that takes notice of and makes claims about fleeting things in situ. “Magazine,” on the other hand—derived from makhzan, an Arabic word for “warehouse”—suggests storage for future use. This sense can come into sharp focus when you consider the “magazine” of a gun, where bullets are stored before being fed into the breech and fired into the field. This is a somewhat dramatic way of thinking of the work of magazines, but it’s also not entirely irrelevant: a collection of (potentially explosive) material put in storage for future use. By simply fulfilling their journalistic function and publishing on a schedule, magazines accumulate a series of pulse-takings and diagnoses: the urgent, daily aspect is offset by a future-oriented warehousing. The best literary organs comprehend this relationship and make each issue relevant to the present and future by taking calculated risks and making strong claims in the kinds of writing they publish. The word “review” contains these functions nicely; meaning, literally, “looking again,” it suggests both action and reflection.[1]

•

Chicago Review’s Spring 1946 inaugural issue lays out the magazine’s ambitions with admirable force: “rather than compare, condemn, or praise, THE CHICAGO REVIEW chooses to present a contemporary standard of good writing.” This emphasis on the contemporary comes with a sober assessment of “the problems of a cultural as well as an economic reconversion” that followed World War II, with particular reference to the consequences this instrumentalizing logic held for contemporary writing: “The emphasis in American universities has rested too heavily on the history and analysis of literature—too lightly on its creation” (CR 1.1). Notwithstanding this confident incipit, CR was hardly an immediate success. It had to be built from scratch by student editors who had to negotiate a sometimes supportive, sometimes antagonistic relationship with CR’s host institution, the University of Chicago. The story I tell here focuses on the labors of F. N. Karmatz and Irving Rosenthal, the two editors that put CR on the map in the 1950s, albeit in different and potentially contradictory ways. Their hugely ambitious projects twice drove CR to the brink of extinction, but they also established two idiosyncratic styles of cultural engagement that continue to inform the Review’s practice into the twenty-first century off to a most calamitous start.

Rosenthal’s is the story that is usually told of CR’s early years: in 1957 and ’58 he and poetry editor Paul Carroll published a strong roster of emerging Beat writers, including several provocative excerpts from Naked Lunch, William S. Burroughs’s work-in-progress; in late 1958, after the Chicago Daily News described CR as “filthy writing,” the Review was suppressed by the University’s administration, and Rosenthal and Carroll and most of their staff resigned and started a new magazine, Big Table, to publish the suppressed material. This is a sensational story and well worth retelling. But we can get a more fine-grained sense of the magazine’s history—and in particular of the magazine’s unique relationship to the University of Chicago—by contextualizing the 1958 convulsion in light of Karmatz’s tenure, which ran from 1953 to ’55. In collaboration with University professors, Karmatz refashioned CR from a modest college magazine into a nationally distributed, closely read organ of intellectual record. Rosenthal, in turn, reinvented Karmatz’s reinvention, presenting edgier fare to the mainstream audience Karmatz cultivated. Their inadvertent collaboration across time created the conditions of autonomy under which the magazine thrives to this day, even as their projects tested the limits of University sponsorship.

Chicago Review has been edited by graduate students at the University of Chicago since its inception. This is, on the face of it, an improbable model for survival. Other university-affiliated journals of CR’s scale and longevity are typically edited by tenured professors, an arrangement that tends to maximize editorial continuity and minimize friction with their host institution. The Kenyon Review, for instance, has had thirteen professor-editors since its inception in 1939; The Yale Review, founded in 1911, has had nine, two of whom edited for more than twenty years. In contrast, CR has had sixty different editors in the last seventy-three years. On hearing these figures, former Yale Review Editor J. D. McClatchy quipped, “What are you, a banana republic?” From the perspective of faculty-edited, university-sponsored journals, CR’s structure may seem labile and unstable. But from another perspective (call it that of the purist outsider), the very fact of university sponsorship is seen to necessarily compromise a journal’s aesthetic integrity. Praising a 2005 issue, poet Ron Silliman wrote that CR’s success “is more or less impossible” given that it is a “college magazine” (his emphasis), and as such, must work against the fact of “typically cautious faculty sponsorships & rotating student editors.”[2] But CR’s unique history reveals that for all its liabilities—and there are those—this structure has been a surprising source of strength that promotes improbable and enduring adaptations and keeps the magazine’s agenda fresh and mobile and free from the predictable programs of more stable editorial models. Devin Johnston, CR’s Poetry Editor from 1995 to 2000, once suggested to me that this structure makes it possible to “combine the university’s intellectual earnestness with an irrepressible enthusiasm (from being young).” Karmatz and Rosenthal proved this in the 1950s, as have CR’s sixty other editors, each in their own ways. May the magazine thrive and expand in new directions for all the days to come!

•

The Review’s first six years were wobbly. Funding was limited and editorial tenures were particularly abbreviated: twenty editors topped the masthead between 1946 and 1958. Edited by students such as Ned Polsky (who went on to write an influential sociological study of pool, Hustlers, Beats, and Others) and V. R. “Bunny” Lang (a poet who became muse and confidante to Frank O’Hara before her early death in 1956), CR’s early issues included fiction by Kenneth Patchen; poems by Paul Éluard, Tennessee Williams, and Karl Shapiro; and critical prose by Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Marianne Moore. There’s a range of contributions from University of Chicago professors and notable alumni: the neo-Aristotelian critic Elder Olson, sociologist Reuel Denney, the nonconformist Paul Goodman (PhD 1954 and author, in 1960, of Growing Up Absurd: Problems of Youth in the Organization System—a signal countercultural text for the decade that followed), and a young Susan Sontag (AB 1951; her first time in print, a review of Harold Kaplan’s novel The Plenipotentiaries [1950], begins with a helpful definition: “Plenipotentiaries, as everyone knows, are diplomatic agents who are endowed with full powers to transact certain weighty affairs of state” [CR 5.1]).

But there was also a lot of chaff—most of it student work—interspersed among the more memorable proceedings. Larzer Ziff (who was then on CR’s staff) described the challenges faced by the start-up student-run magazine:

When we went out in search of material and wrote asking established writers to give us something although we couldn’t pay we sometimes received interesting pieces. We also, of course, read unsolicited manuscripts and published those that attracted us, but I feel there was always too wide a gap between the two and so an unevenness amounting to uneasiness in our pages.[3]

Money was a constant source of concern. Albert N. Stephanides, another early staffer, remembered the Review’s bakesale-style fundraising:

Our main problem in those days was to raise enough money to bring out an issue. The only material aid we had from the University was use of office space in the Reynolds Club and the right to use classrooms in the evenings as part of our fundraising. Our main sources of fundraising were to persuade popular U of C professors of the day to give lectures (gratis to us, charged to attendees) and to show movies.[4]

The journal’s format in its first six years reflects this scarcity of funds. Most issues were saddle-stapled chapbooks of roughly fifty pages. During one especially dry stretch the format switched to eight-page newsprint for two issues (CR 3.1 and 3.2). Circulation was modest as well; fewer than 700 copies were printed of any given issue, and distribution was primarily local.

All this changed with the Spring 1953 issue. This handsome ninety-six-page perfect-bound book with a conspicuous logo marked the arrival of F. N. “Chip” Karmatz, who presided over the Review for three years (nine issues in all) and gave the magazine a welcome sense of direction, focus, and substance. He solicited and published well-known authors and critics and set a strong precedent for engagement with contemporary US culture. Just as significantly, he created a robust national distribution system, which placed the magazine’s circulation in another league altogether. George Jackson, on staff for most of the 1950s, remembered Karmatz as the Editor “who turned the Review from a campus literary magazine into a major quarterly” (CR Records, 60:5). Lucy B. Jefferson recollected that he was “determined to get the Review up there with The Sewanee Review and others of the ‘respectable academic journal’ class” (CR Records, 60:5). It’s clear he did just that: by Spring 1955 Karmatz could proudly announce to his readers that CR had “the largest circulation of any cultural quarterly or ‘little’ magazine” (CR 9.1).

The titles of two special issues published during Karmatz’s tenure—“Contemporary American Culture” (CR 8.3) and “Changing American Culture” (CR 9.3)—accurately denote the focus of the Review at the tail end of the McCarthy Era. “I did everything I could to keep the Chicago Review apolitical or neutral,” Karmatz told me in 2005. “We were a cultural publication, open to all cultural viewpoints.”[5] This liberal pluralism is reflected in the pieces Karmatz published by artist Ben Shahn, political philosopher Leo Strauss, psychologist Bruno Bettelheim, and banned novelist Henry Miller; other essayists treat topics ranging from Abstract Expressionism and Brown v. Board of Education to Ludwig Wittgenstein and Alfred North Whitehead. Karmatz’s upgrade also included art by Paul Klee and Pablo Picasso; poems by William Carlos Williams, e. e. cummings, Paul Valéry, and Henry Rago (Editor of Poetry from 1955–1969); and fiction by Nikos Kazantzakis, Mark Van Doren, and Philip Roth (his first story in a major periodical). CR–sponsored readings at the University by poets such as Edith Sitwell and e. e. cummings (Dylan Thomas died a few days before his scheduled reading) contributed to the considerable cultural prestige CR was accumulating, and generated necessary revenue for the journal’s increasingly ambitious print runs.

F. N. “Chip” Karmatz (right) and staff at a Chicago Review meeting in 1954.

Karmatz also injected memorable energy into the business of editing the magazine. George Starbuck, who joined the staff toward the end of Karmatz’s tenure, recalled the charismatic boss:

If he had a fedora, it would have been crushed, worn on the back of his head, and thrown, on occasion. He liked to sit in the Chicago Review offices with his shirt unbuttoned and his tie on but askew, handling two phone calls at once, East and West coasts, because nobody had told him he couldn’t badger e. e. cummings for poems or Rexroth for a think piece.[6]

George Jackson noted new modes of moneymaking that Karmatz devised to fund his renovation:

The ways in which Karmatz managed the transformation were ingenious and amusingly devious. One tactic was to slick down his hair, put on his leather coat, turn up his big collar and with his best gangster manners visit neighborhood merchants to solicit ads for the Review. [CR Records, 60:5]

Karmatz told me that this appealing lore was somewhat overstated—he only had one phone, never published Rexroth, and everyone on staff sold ads locally—but his energetic presence, and the influence it had on his staff, is amply evident.

The good working relationship between Karmatz and his staff was complemented by his fruitful collaborations with CR’s faculty advisors, Gwin Kolb (Professor in English) and Reuel Denney (in Sociology). Karmatz was especially close with Denney, 1939’s Yale Younger Poet and coauthor of The Lonely Crowd (1950), a groundbreaking, bestselling analysis of conformity and individuality in the postwar US. Denney secured the Murphy Scholarship in Journalism for Karmatz, a bequeathed fund that had not yet been tapped and which sustained several editors after Karmatz (including Rosenthal).[7] Karmatz and Denney were tennis partners, and a folder in the Denney papers at Dartmouth College traces the brainstorming sessions that transpired between them. Most of these notes focus on the “new model” Review that emerged under Karmatz: lists of potential contributors, distribution strategies, circulation figures for CR in comparison to other little magazines, and a parsing of CR’s efficient cause, formal cause, material cause, and final cause (neo-Aristotelianism was all the rage at the University in those days). There are several documents focusing on staff structure and training, but it is worth noting that faculty oversight is mentioned only once in passing:

PURPOSE: To produce a quality magazine that can compete and compare to standards of any literary journal of good literary quality, under the auspices of the University, namely the faculty advisor, Gwin Kolb.

This is the first paragraph of a four-page typescript describing the magazine’s “purpose,” “policy,” “organization,” and editorial criteria. The document ends with a note that suggests that both editor and faculty advisor had their attention focused on the magazine’s promise, rather than on the structure and details of oversight: “At all times the primary goals of quality and stability should be kept in mind. It should also be kept in mind that the magazine should be self-sustaining.”[8] That these papers are located in Denney’s archive indicate the extent of his beneficial involvement in “the viability of the operation”[9]—an involvement that was apparently so seamless and healthy as to not require consideration of possible antagonisms or conflicts of interest.

The fuzziness of this relationship worked well for Karmatz. “Editorially, if Gwin Kolb or Reuel Denney OK’d a particular issue’s content,” he explained to me, “Dean [of Students] Strozier allowed the publication to go ahead. However, I don’t think this was a formal process and I am not aware of the communication between them.”[10] Karmatz told me that CR was defined as “a student publication endorsed by the Administration”:

Strozier simply covered our printing debts, if there were any, for any given period. […] The budget was part of a student services fund. Dean Strozier never explained how it worked—wasn’t student business.[11]

This opacity was unproblematic for the duration of Karmatz’s tenure, but it led to an almost fatal crisis shortly after his editorship ended. A notice in the Chicago Tribune’s “Literary Spotlight” set the scene: “Chicago Review, the quarterly owned by and published at the University of Chicago, recently issued its second annual copy, devoted to ‘Changing American Culture,’ in a special printing of 22,500 copies.”[12] Karmatz had his reasons for this optimistic print run (exactly twice the circulation of Partisan Review, the largest little magazine of the day): he was anticipating an essay by former President Harry Truman. It fell through, but a new distributor remained sanguine and the print run was not adjusted.[13] A massive printing bill arrived several months later in tandem with a flood of unsold copies, long after Karmatz had graduated and passed on the Review’s editorship. The Dean of Students threatened to close down the magazine rather than pay the bill, but Karmatz’s faculty colleagues interceded on CR’s behalf.

Denney and Elder Olson (a professor who, like Denney, was both a longtime supporter of the Review and an occasional contributor) convinced Dean of Humanities Napier Wilt to assume direct administrative and financial responsibility for CR. Two years after this crisis, Wilt explained the changes:

Since the spring of 1957, when the Dean of Students in the University asked to be relieved of fiscal responsibility for the Chicago Review, the magazine has been “located,” administratively, under the Division of the Humanities and of the college. The change was made to ensure continuation of the Review at a time when its future was precarious.[14]

The newly installed Faculty Board “was to serve solely as a ‘financial watchdog’ and was to have no voice in editorial policy” (as Albert N. Podell put it in San Francisco Review in 1959).[15] David Ray, one of Karmatz’s successors, had argued to the University administration that

Editorially, one of the strong points of the magazine has been its freedom and independence. Comparing magazines subsidized by other universities and edited largely by university faculties, one notes a dryness the Review has never encouraged. I, for one, would hate to lose this strength by an overly strong faculty supervision.[16]

The fiscal relocation and the formalization of faculty oversight of CR’s finances saved CR, but it also drew the magazine more closely into the University’s administrative orbit, establishing conditions for a crisis of a different sort.

•

If little magazines are barometric instruments, as Lionel Trilling described them, then editor Irving Rosenthal (whose one-year tenure began in 1957) produced a magazine that made as much weather as it measured.[17] Where Karmatz successfully emulated the stately Sewanee and Kenyon reviews edited by New Critics Allen Tate and John Crowe Ransom, respectively, it was the younger, hipper Evergreen Review edited by Donald Allen (who would go on to edit the monumental New American Poetry anthology) and the avant-garde Black Mountain Review edited by Robert Creeley that captivated the editorial imaginations of Rosenthal and Poetry Editor Paul Carroll. With these models in hand, Rosenthal and Carroll effected a reconversion of CR’s intellectual energy, shifting the focus from analysis of a “Changing American Culture” to actually changing American culture by publishing Beat writers reacting perpendicularly to the postwar culture Karmatz and his successors had so acutely parsed.

In an essay on “The Role of the Writer and the Little Magazine”—published two issues before Rosenthal took the helm—University of Chicago professor and novelist Isaac Rosenfeld staked out a staunchly heretical position that anticipated this shift in the magazine’s self-fashioning:

I am used to thinking of the writer […] as a man who stands at a certain extreme, at a certain remove from society. He stands over against the commercial culture, the business enterprise, that whole fantastic make-believe of buying and selling they would have us believe is the real world. [CR 11.2, p. 4]

Rosenfeld did not spare CR from his assessment of the baleful affiliation between little magazines and the academy. But in the following issue Carroll ratcheted up Rosenfeld’s rhetoric and bluntly named names, initiating a dissent different in kind from what the Review had published to date:

[R]eading some of the recent Yale younger poets, the Lamont prize winners, and, say, an anthology like Mr. Richard G. Stern’s tidy, judicious American Poets of the Fifties (Western Review, Spring 1957), one becomes spooked by the image of the young poet prematurely corseted with aldermen, thinning hair, tenure, and routine no-nonsense sex life. Cozy middle-aged verse. Absent are most of the expected vices and virtues of the young poet: no technical howlers; no tears for a lost garden of earthly delights; no ranting and raving against the established society; no bumptiously imperative subjective moods. Able, academic, anemic verse instead. [CR 11.3, p. 76]

A few factors put Carroll’s “Note on Some Young Poets” in a sharper, more personal light: he had, in fact, been published in the very anthology he so vehemently decries, and the anthologist, Richard Stern, was a young novelist and new professor at the University of Chicago who had recently been appointed CR’s faculty advisor in the wake of Karmatz’s overoptimistic print run. The intimacy of the attack is exacerbated further still by the fact that Carroll’s “Notes” were printed directly after an essay by Stern on the poet Edgar Bowers. Where Karmatz played tennis with CR’s faculty advisor, Carroll enters into a competition of an altogether different sort. In light of such brinksmanship, it seems a showdown with the University was inevitable.

Irving Rosenthal, who became CR’s editor with the next issue, turned the spasms of agitation articulated by Carroll into a full-fledged editorial program. Carroll remembered Rosenthal saying he wanted “‘only the best poems’ and to hell with literary politics or equal representation of all schools of contemporary poetry” (CR Records, 60:5)—a pointed contrast to Karmatz’s pluralist ideal. And Rosenthal shared Carroll’s knack for controversy. In a September 1957 letter to Vladimir Nabokov he writes, “I would […] very much like to know […] the censorship story over Lolita” (CR Records, 29:3).[18] Within a month, another highly publicized censorship story would come to a close in San Francisco: on October 3, 1957, Judge Clayton Horn dismissed the obscenity case against City Lights publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti for publishing Allen Ginsberg’s Howl.

Finger on the pulse, Chicago Review’s Spring 1958 issue featured a constellation of “Ten San Francisco Poets.” In addition to Ginsberg and Ferlinghetti, this issue included poems by Jack Kerouac, Robert Duncan, John Wieners, Michael McClure, Philip Lamantia, and Philip Whalen—the nucleus of the “San Francisco Scene” and an unmistakable antidote to the “anemic, academic verse” Carroll had deplored.

Cover of CR 12.1 (Spring 1958)

The thrust toward immediacy was explicit in one of Ginsberg’s poems:

Stop all fantasy!

live

in the physical world

moment to moment

I must write down

every recurring thought—

stop every beating second

[CR 12.1, p. 11]

Kerouac’s preface, “The Origins of Joy in Poetry,” called this new work “a kind of new-old Zen lunacy poetry,” which he contrasts explicitly with that “lot of constipation,” “the [T.S.] Eliot shot” (ibid., p. 3). Along with these new poets, Rosenthal and Carroll published the first chapter of Burroughs’s Naked Lunch, which came to CR’s attention via correspondence with Ginsberg:

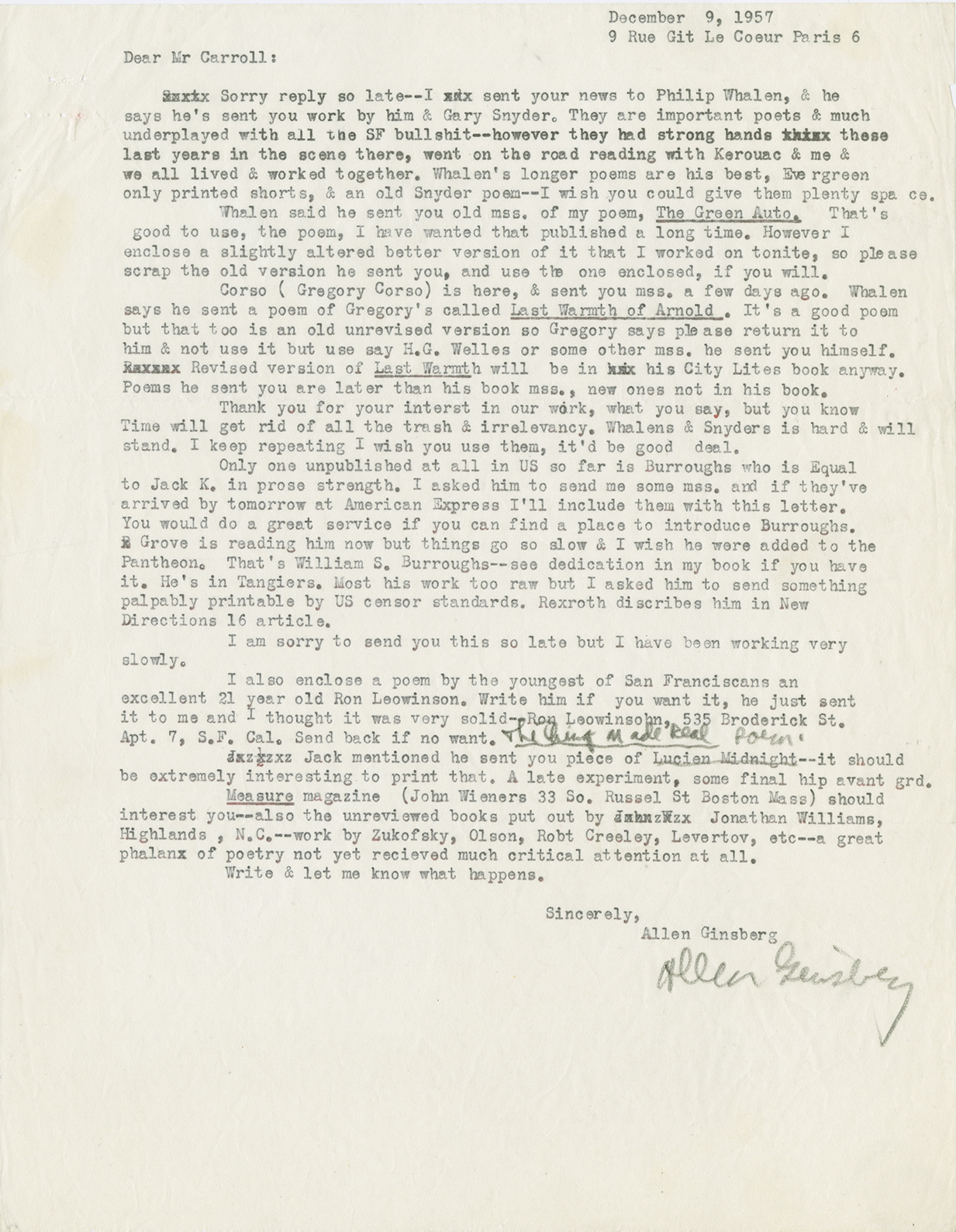

Only one unpublished in US so far is Burroughs who is equal to Jack K. in prose strength. […] You would do a great service if you can find a place to introduce Burroughs. […] He’s in Tangiers. Most of his work is too raw but I asked him to send something printable by US censor standards. [CR Records, 24:5]

Two weeks later another letter from Ginsberg arrived, this one less cautious about the raw and the cooked:

Don’t worry about what people will say if you turn out a screwey [sic] magazine full of idiotic poetry—so long as it’s alive—do you want to die an old magazine editor in a furnished room who knew what was in every cup of tea? Put some arsenic in the magazine! Death to Van Gough’s [sic] Ear!

Help!

ALLEN GINSBERG

Ah! I forgot—I also enclose some final poison for your pot—Burroughs! He sent me this excerpt this week. [CR 12.3, p. 49]

Burroughs’s close-to-the ground account of the life of a junkie on the run begins, “I can feel the heat closing in, feel them out there making their moves,” and you certainly can: by the end of the year the University of Chicago would suppress CR for printing one toxic excerpt too many from Naked Lunch (ibid., p. 25).

Paul Carroll (left) and Allen Ginsberg (right) in 1959.

The Review’s San Francisco issue strongly resembles the Evergreen Review’s influential 1957 feature on “The San Francisco Scene”—though the inclusion of Burroughs makes it a wager of a different order.[19] CR had a more established audience than the Evergreen Review, and was able to lend the prestige of a strongly reputed, University-sponsored journal to the Beats’ fledgling program. Perhaps for this reason, “Ten San Francisco Poets” attracted considerable attention from the national media. None of it was favorable. The New York Times Book Review of April 6, 1958, quoted Kerouac’s preface en toto, then asked, “All clear now?”[20] A month later in the Book Review J. Donald Adams reported, “This spring the Chicago Review devoted a good part of its issue to the presentation of ten San Francisco poets, and I have been unable to find a memorable poem among them.”[21] The Nation, for its part, includes the issue in its “Post-Mortem on San Francisco.”[22]

The caption to a photo of a beatific and bearded Rosenthal and staff for a 1958 Chicago Tribune spread calls CR a midwest “Beat” outlet, and faculty dismay at the association was evident.[23] According to Rosenthal, Stern had warned him not to “turn Chicago Review into a magazine for San Francisco rejects,” adding, “This is as if garbage had garbage.”[24] After Ginsberg’s “poison for your pot” letter was published in the magazine, University Chancellor Lawrence Kimpton complained, “Even the business correspondence of these authors were sacred.”[25]

Clockwise from front: Irving Rosenthal, Doris Nieder, Hyung Woong Pak, Barbara Pitschel, and Eila Kokkinen.

Rosenthal and Carroll’s correspondence with Ginsberg and other authors exposes an avid avant-garde self-consciousness. In a 1959 letter to Creeley, Carroll described Ginsberg’s style of correspondence: “Allen G writes long epoundian epistles, full of care & love & total commitment, trying to turn me on to one young poet or another.”[26] Reflecting on Ginsberg’s role in a letter to Carroll in early 1959, Rosenthal makes the analogy explicit: “Allen Ginsberg will at least do as much for literature as Pound did.”[27] Even if this prediction has proven extravagant, Ginsberg’s letters to CR do have an energetic force similar to Pound’s correspondence with two earlier editors of Chicago-based magazines, Harriet Monroe of Poetry and Margaret Anderson of The Little Review. Part annotated address book, part forceful interpretation of new work, Ginsberg’s letters show a poet acting as agent and advocate for his coterie:

You must dig, that certain poems which appear at first formless like Jack Kerouac’s or Corso’s have either their own form which will be apparent with long familiarity with that style—or else the poet is looking for something else than new metrical form or nonmetrical form—Corso for instance is often interested in pure ellipsis, that’s his kick, you see—or Kerouac interested in the flow of his mind—these are all experiments—you must not judge them by the standards of already written poetry, recognizable standards—the poems have to create standards of their own.[28]

Willing as Carroll and Rosenthal were to work with these writers, they were not shy to reject some of the new work coming their way. A Rosenthal letter to Creeley shows an enviable candor and vulnerability:

I am also returning a poem called “The Way,” which, as you can see, came even closer to publication. I understand your stories better than your poems, yet you should send your poems too. I think it’s a matter of an editor adjusting to a writer, and I’m on the verge of liking your work well enough, and so you might help by supplying it. [CR Records, 12:4].

Here we see Ginsberg’s inductive imperative—“the poems have to create standards of their own”—taking hold. To his credit Creeley did supply more writing to Rosenthal. His essay “Olson and Others: Some Orts for the Sports” arrived just as the crisis over the University’s suppression started unfolding; it traveled with Carroll and Rosenthal to Big Table, where it was published in Spring 1960 (and was subsequently reprinted in Donald Allen’s New American Poetry).[29]

Notwithstanding the negative publicity from the national press (and quite likely facilitated by it), CR’s “Ten San Francisco Poets” went into a second printing, and Rosenthal turned his attention to a related, though less incendiary, topic: Zen Buddhism. The first anthology of its kind in the US, CR’s Zen issue suggests that, in addition to a knack for controversy, Rosenthal had a keen intuition for emerging, influential ways of thinking.

Carroll remembered learning of the issue:

One day I waltzed in to see [Rosenthal] and discovered that the office had been swept clean of manuscripts, books, posters; in their place was a solitary peacock feather protruding straight out next to a small printed sign: “Think Zen.” I’d heard of Zen but knew nothing about it; most of the other editors were in the same boat. Before we had a chance to ask, Irving, all 5’1” with a beard almost as tall as he was, announced that Alan Watts was coming to the University at his invitation to give a series of lectures. [CR 42.3/4, p. 48]

Anchored by Alan Watts’s critical essay on “Beat Zen, Square Zen, and Zen” (a less than flattering appraisal of the Beat appropriation of Zen), the Summer 1958 CR included items by three Beat poets—Kerouac, Whalen, and Snyder—and essays by D. T. Suzuki and eight others. Non-Zen material was non-controversial: reproductions of art by Franz Kline, an excerpt from Samuel Beckett’s The Unnamable, and a combative review by Charles Olson of a recent book on Melville.[30]

This issue, too, made it into the national weeklies, to much greater acclaim. The Nation mentioned CR favorably in an article on “The Prevalence of Zen.”[31] And in a flattering profile of Alan Watts, Time observed that “Zen Buddhism is growing more chic by the minute. Latest evidence: the summer issue of Chicago Review.”[32] A few weeks later Rosenthal wrote Kerouac: “we hit Time boyoboy didn’t we. It would be really immodest of me to tell you what the Zen issue did to our circulation” (CR Records, 16:2).

Cover of CR 12.2 (Summer 1958).

Buoyed by this heady success—the issue sold more than 5,000 copies—Rosenthal set up two lectures on campus—Watts in November, Ginsberg in December—and went to work on the Naked Lunch manuscript he had recently received via Ginsberg:

Left Bill Burroughs in Paris, now I hear he’s ill & taken off to kick in Spain. The long mss. you’re publishing is finished, in messy sections & fragments, and he’s been putting it, assembling it, for you—don’t know how far he’s gone. It overlaps, sometimes, a 400 page mss. […] composed of finished but discontinuous fragments. […] You would find there a huge mass of publishable material—tho much obscene, probably too much for your uses. [CR Records, 13:2]

Obscenity notwithstanding, in June 1958 Rosenthal wrote to Burroughs, “Chapter III is so good I want to lead with it, and your name on the outside cover” (ibid.). And that’s exactly what he did.

This Burroughs excerpt, published in CR’s Autumn 1958 issue, was more subcutaneous and outré than the first:

She seized a safety pin caked with blood and rust, gouged a hole in her leg which seemed to open like an obscene festering mouth waiting for unspeakable congress with the dropper which she now plunged out of sight into the gaping wound. [CR 12.3, p. 4]

There’s pus, miasma, evil, bugs, meat, cocaine and nembies, alligators and bats, pimps and judges, narcotics commissioners and schizophrenic detectives: “episodism, to coin a word, under complete control,” Rosenthal wrote to Burroughs (CR Records, 16:2). A dealer named Lupita opines that “Selling is more of a habit than using” and a desperate buyer kisses his District Supervisor’s hand, “thrusting the fingers into his mouth,” and begs, “Please Boss Man. I’ll wipe your ass, I’ll wash out your dirty condoms, I’ll polish your shoes with the oil on my nose.” The ten-page chapter ends with an ominous “To be continued”: Rosenthal was preparing to publish another excerpt in the Winter 1959 issue, along with prose by Kerouac and Edward Dahlberg.

Cover of CR 12.3 (Autumn 1958).

That issue never appeared. On October 25, a few weeks after the Autumn 1958 issue was published, Chicago Daily News’s popular front-page “bluenose” columnist Jack Mabley denounced the “dangerous” Review as “evidence of the deterioration of our American society.” His column—titled “Filthy Writing on the Midway,” and accurately subtitled “Jack Rips Mag”—begins:

Do you ever wonder what happens to little boys who scratch dirty words on railroad underpasses? They go to college and scrawl obscenities in the college literary magazine.

There’s misinformation and histrionics in the column: he thinks the authors published in CR are University of Chicago students, and he refuses to name the magazine, “because I don’t want to be responsible for its selling out.” But for all that, Mabley’s last sentences would have been difficult to mistake or ignore:

I don’t put the blame on the juveniles who wrote and edited this stuff, because they’re immature and irresponsible. But the University of Chicago publishes the magazine. The Trustees should take a long hard look at what’s circulated under this sponsorship.[33]

Reading this a few days later in the Review’s offices Carroll quipped, “‘A long, hard look’—Irving, we have to get him to write for us!”[34] But that last sentence found its mark. The University was saddled with substantial debt from the years under Robert Maynard Hutchins, the University’s Chancellor from 1929 to 1951 whose “extramural politics,” “pro-labor sympathies,” and “doctrinaire defense of academic freedom” (as historian John Boyer put it) had tested the patience of the University’s Trustees and drawn the unwelcome attention of conservative millionaires and red-baiting Congressmen.[35] Hutchins’s rather more staid successor Lawrence Kimpton, former VP for Development, had joined the University as chief administrative officer of Enrico Fermi’s “Metallurgical Laboratory” (which inaugurated the Nuclear Era by producing the first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction) and was “an adroit fundraiser” who understood all too well the weight of public opinion.[36]

Mabley’s obscenity charge couldn’t have come at a more inopportune moment. Kimpton’s controversial urban renewal plan for Hyde Park (the University’s immediate neighborhood), cosponsored by Mayor Richard J. Daley, was almost complete, but needed the approval of the City Council. Mabley’s spotlight on CR threatened the already delicate balance between the University, the City of Chicago, and the Catholic Church (which had been scrutinizing the plan and making both University and City squirm). As it happened, the infamous renewal plan was approved in early November 1958, and it’s tempting to speculate that CR’s suppression was a collateral consequence of that process.

A pair of memos preserved in Kimpton’s archives indicates the tenor in which the crisis was transacted in his offices. One describes a phone call from Kimpton’s point man on the urban renewal campaign:

Julian Levi telephoned at 4:45 pm to report that […] Hyde Park Police […] picked up a 13-year-old boy carrying a copy of the Chicago Review. The boy is suffering—also—from syphilis […]. The magazine has been sent to the Chicago Police Youth Bureau […]. More action probably can be expected.

The other is a memo from the University’s legal department. Following Mabley, it labels CR “filth” and anticipates serious challenges in fundraising and public relations more generally:

The magazine contains filthy and obscene language that is associated with the gutter rather than with a literary publication of an institution of higher learning. […] How this filth could be published in what must be regarded as a University publication will be very difficult for the public to understand. We think that this incredible publication will have a very serious effect upon fund raising, enrolment [sic] and our public relations generally.[37]

Sure enough, in the wake of Mabley’s column Kimpton received a flood of letters, including an incisive three pages on Great Lakes Solvents letterhead:

Obscenity is not just dirty words. It is action that took place “off scene” in the theatres of antiquity. It is the vulgarity and ugliness of real life which a society that still has a respect for values shields from public view. Just because garbage cans behind our house are necessary concomitants of human life, must we go sit in them? […] We businessmen are busy, but not too busy to think about the consequences of ideas in gestation in our universities. As you know, we are continually asked to contribute corporate funds to universities.

Kimpton passed this letter on to Dean of Humanities Napier Wilt: “I attach a fan letter of a somewhat more thoughtful kind than I have been receiving. It really is hurting us with some rather superior people.”[38]

Dean Wilt was, according to Rosenthal, “the Review’s strongest backer on faculty”; he had, after all, helped save the magazine two years earlier when Dean Strozier threatened to close it after receiving the bill for Karmatz’s last issue.[39] But Kimpton’s authority was meteorological. “When it rains,” Wilt told Rosenthal, “you have to put on a raincoat.”[40] Rosenthal had already delivered the Winter issue to press when he received Wilt’s unambiguous instructions: “The winter issue must be completely innocuous” (CR Records, 16:2). If it wasn’t, Wilt made clear, the Review would be shut down for good.

Referring to the “anomalous position” of having a student-edited magazine “owned by the University but not under its supervision” (CR Records, 5:3). Kimpton told the Review’s Faculty Board that “the legal situation is intolerable.”[41] Faced with the Board’s unwillingness to abrogate CR’s editorial autonomy—an unsigned memo to Kimpton confirmed that the board “basically regards itself as an auditor of finances”[42]—Kimpton “felt that he himself would have to take the onus of some action. He felt that the University ownership of the periodical forced this on him” (this according to Reuel Denney as quoted in the University’s student newspaper, the Maroon).[43]

Kimpton told the Committee of the Council of the Faculty Senate (the University’s governing body) that “some remedial action should be taken” because there was

reason to believe that the tone of the new issue will be gamier than the number presently under consideration. To publish such copy under present conditions […] would result in further attacks by the press.[44]

A month later, after the suppression, Kimpton told the Maroon a different story: “the Review was clearly in a rut” and Rosenthal was “completely infatuated with the San Francisco school to the point that he deemed no one else worth publishing.”[45] But Chicago Review was in peak performance when the University suppressed it. The multiple printings of both the San Francisco and Zen issues brought in enough income that Rosenthal could, for the first time in the Review’s history, promise payments to his contributors. A week after Mabley’s column was published, CR hosted three well-attended lectures on Zen by Alan Watts. Moreover, CR had an ambitious range of issues in planning stages at the time of the suppression: Barbara Pitschel had made significant headway with an issue on German Expressionism and Doris Nieder had begun soliciting authors for an issue on “New British Writing” (CR Records, 18:2 and 18:3).

For all that, Rosenthal had a keen sense of just where things stood. The faculty board may have understood the limit of its authority as a “fiscal watchdog,” but the University’s Chancellor could and would do as he pleased. In a dramatic letter to former Chancellor Hutchins, Rosenthal confirmed Kimpton’s estimation of the forthcoming issue: “I do not at this point see how I can publish an issue with the criterion of innocuity. As we’ve got it planned, it won’t be innocuous.” But his letter also indicated his willingness to compromise: “I am willing to suppress it as an issue of the Chicago Review, if it means the magazine will not be killed” (CR Records, 16:2).

Rosenthal to R. M. Hutchins, November 15, 1958. CR Records, 5:3.

Three days later—three weeks after Mabley’s column had appeared—Rosenthal called a staff meeting. As recorded in the minutes of this “tense three-hour meeting,”[46] Rosenthal

informed the staff that it was his understanding that the very existence of the Review was at stake. He explained to the group that the University administration had informed him that if the magazine were to continue it must be under the following conditions:

(1) The next issue must be of a non-controversial nature.

(2) The Review must be subject to an annual appraisal by the faculty committee of the magazine.

(3) In the future the editor shall check with the faculty committee before publishing any manuscripts which he thinks might be objectionable.

Mr. Rosenthal said that he was told that if the magazine did not comply with these stipulations, it would in all probability be discontinued by the University of Chicago.

Rosenthal went on to propose two options for the Review: either refuse to comply with the University’s conditions (and risk closure of the magazine) or “elect a new editor of the Review who could publish in good conscience” an issue acceptable to the University. Only one staff member, Hyung Woong Pak, felt that he could put together an acceptable issue in good faith; the staff voted 15-2 for the second option and elected Pak editor. Rosenthal and the rest of his staff resigned and (a few months later) founded Big Table to publish what had been suppressed.

In early 1959 the University of Chicago’s Student Government issued a twenty-three-page report on CR’s suppression. Its conclusions were blunt and severe:

The resignation of the editors and the failure of the Winter issue to appear were both due to pressure imposed by the Administration on the editors. The University threatened to prevent publication of the Review if the editors attempted to print manuscripts which might cause further adverse press comment about the University. […] The principle reason the University imposed pressure on the editors was that the University itself was under pressure from persons financially interested in the University to prevent the appearance of another such issue. […] The primary reason for the University’s actions was concern over public reaction to the use of obscene expressions in literature, and the other reasons are a posteriori justifications for that action. […] [T]he Administration and Faculty have an obligation […] to insist vehemently on the independence of student judgments from outside intimidation and threats. In working to encourage the intellectual growth of its students, the University must provide the atmosphere for new ideas to be tried, new views to be expounded. It is this atmosphere which we feel is most seriously challenged by the Chancellor’s capitulation to the whim of the local columnist. (emphasis in original)

Although the administration made much of CR’s “anomalous position” in the immediate aftermath of the suppression, there were no changes in CR’s structural relationship with the University. Pak told the Maroon: “I am free and everything is up to me. I am free to print whatever I damn well please. As editor of the Chicago Review I have complete autonomy and the complete right to print whatever I choose.”[47] Pak’s successor Peter Michelson remembered that Pak “had little to fear from the faculty, who had been so badly burned by the censorship controversy that they were more than happy to keep hands off.”[48] Pak reverted to the relatively safer territory of the Karmatz years (his first issue was on “Existentialism and Literature”), but by the mid-1960s CR had sloughed any unseemly residue of Kimpton’s suppression.

Irving Rosenthal with the Chancellor’s cat.

Rosenthal played a high-stakes game in publishing so much Burroughs. But in so doing, he also participated in the ambitions of Karmatz-vintage CR. The last sentence of the introductory note to 1954’s issue on “Contemporary American Culture” could just as well apply to the magazine Rosenthal edited: “The Review, as a quarterly of ideas and creative literature, is […] an attempt to place genuine literature before an audience capable of carrying out its own processes of ratiocination” (CR 8.3)—a serious, considered, and sometimes risky enterprise, in other words, that holds the state of the art and the intelligence of its audience in high esteem, regardless “the whim of the local columnist.”

The Chicago Review Anthology, published in 1959 by the University of Chicago Press, excludes any trace of CR’s Beat episode from its pages. But it does conspicuously foreground Isaac Rosenfeld’s “The Role of the Writer and the Little Magazine.” In his review of the Anthology in The Nation, Nelson Algren wrote that Rosenfeld “knew that the artist is the man who endures society’s hostility and even its scorn in order to point out the sickness at its heart.”[49] It isn’t hard to recognize that Naked Lunch belongs precisely to this tradition of writing that interrogates convention and upsets entrenched habits in order to gain critical leverage on an otherwise intractable set of practices and assumptions. I wish this were an argument original to me. But it is articulated in exactly these terms by none other than Judge Julius Hoffman in his 1960 decision to release Big Table 1 (which contained “The Complete Contents of the Suppressed Winter 1959 Chicago Review”) from the US Postmaster General’s quarantine. Naked Lunch’s “dominant theme or effect,” Hoffman wrote, is to “shock the contemporary society, in order perhaps to better point out its flaws and weaknesses.” Citing Judge John M. Woolsey’s landmark 1934 decision lifting the ban on Ulysses, Hoffman concludes that “clinical appeal is not akin to lustful thoughts.”[50]

Judge Hoffman is better remembered for a less happy relationship to free speech: in 1969 he ordered that Black Panther Bobby Seale be bound, gagged, and chained to a chair during the conspiracy trial of the Chicago Eight that followed the 1968 Chicago Democratic National Convention. Burroughs was sufficiently habilitated into the mainstream by then to be dispatched to Chicago by Esquire to report on the Convention and the bloody anti–Vietnam War riots surrounding it. He appeared on the cover of Esquire’s November 1968 issue, exactly ten years after CR had been suppressed for trying to publish one excerpt too many of Naked Lunch. “A functioning police state,” he writes in that book, “needs no police.”

A Note on Further Reading

The best unfiltered source for contemporary reactions to CR’s suppression is the University of Chicago’s student-run newspaper, the Chicago Maroon; see especially the issue dated 12 December 1958. The 28 January 1959 “Report of the Special Committee of the Student Government in re: Chicago Review” offers valuable analysis and interpretation, as well as interviews with the principals (there is a copy in CR Records, 5:3; Leon Kass, formerly George W. Bush’s bioethicist, was on the Student Government committee). Former CR staff member Albert N. Podell’s piece “Censorship on the Campus: The Case of the Chicago Review” (San Francisco Review 1:2, Spring 1959, pp. 71–87) is similarly packed with useful details. And Rosenthal’s introduction to Big Table 1 (1959, pp. 3–6) offers testimony from the horse’s mouth (it has been conspicuously razored out of the University of Chicago’s circulating copy of Big Table). Former CR editor Peter Michelson, who succeeded Rosenthal’s successor Hyung Woong Pak, reflects on the suppression and its aftermath in “On The Purple Sage, Chicago Review, and Big Table” (TriQuarterly 43, Fall 1978, pp. 341–75). Gerald E. Brennan’s meticulously detailed two-part investigative piece, “Naked Censorship: The True Story of the University of Chicago and William S. Burroughs”—likely the definitive account of the 1958 episode—was published in the Chicago Reader 29 September and 6 October 1995. Richard Stern, chairman of CR’s Faculty Board in 1958, has written about the episode in his “Monologue” in What Is What Was (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002). It must be said that all of these pieces, like the one I have written, reflect the authors’ embedded biases in one way or another.

Notes

I owe a special debt of gratitude to the several friends and colleagues who have given me feedback as I wrote this essay, especially Hannah Woodroofe, F. N. Karmatz, Alastair Johnston, David Keegan, Adam Weg, W. Martin, Gerald Brennan, Devin Johnston, Irving Rosenthal, Adam Fales, Cynthia Huang, and Nabel Wallin. Joshua Kotin and Robert P. Baird, the pair of editors charged with CR’s care when this piece was published in 2006, offered decisive, eagle-eyed comments. Eric Powell and the current CR team have effortlessly stewarded this iteration into the aether. The patient, persistent staff of the University of Chicago’s Regenstein’s Special Collections were endlessly resourceful as I researched the illuminating manuscripts and correspondence in CR’s archive; thanks to David Pavelich and Kerri Sancombe, in particular. Sebastian Hierl originally commissioned the essay, and Srikanth Reddy was an early, helpful reader: I thank them for the opportunity and for their advice. That version was published in From Poetry to Verse: Essays on the Making of Modern Poetry (Chicago: The University of Chicago Library, 2005).

[1] What follows is a revised version of an essay with the same title that was published in CR’s sixtieth anniversary issue (52.2/3/4, 2006). It is reprinted here on the occasion of the sixtieth anniversary of Big Table 1 and in anticipation of CR’s seventy-fifth anniversary in 2021.

[2] Silliman’s Blog, July 26, 2005: https://ronsilliman.blogspot.com/2005/07/alice-notley-another-piece-overpraises.html

[3] CR 42.3/4 (1996): 225. In 1996, on the occasion of CR’s Fiftieth Anniversary, editor David Nicholls contacted several former editors, staff-members, and contributors for reflections on their time at CR. Selections from this invaluable correspondence were included the Fiftieth Anniversary issue (42.3/4); the complete correspondence has been archived in CR’s papers in the Regenstein Library’s Special Collections Research Center at the University of Chicago.

[4] Albert N. Stephanides to David Nicholls, 14 February 1996. Chicago Review. Records, Box 60, Folder 6, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago. Hereafter cited parenthetically as CR Records, [Box #:Folder #].

[5] Karmatz, correspondence with the author, 6 April 2005.

[6] “Wonkiness,” in An Unsentimental Education: Writers and Chicago, ed. Molly McQuade (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1995), 176.

[7] Rosenthal describes the benefits of the scholarship in his “Report to the Faculty Committee: October 7, 1957.” MS 781, 2:58, Reuel Denney Papers, Rauner Special Collections Library, Dartmouth College.

[8] Untitled typescript. MS 781, 2:48, Reuel Denney Papers, Rauner Special Collections Library, Dartmouth College.

[9] Karmatz, correspondence with the author, 20 April 2005.

[10] Karmatz, correspondence with the author, 6 April 2005.

[11] Karmatz, correspondence with the author, 2 April 2005.

[12] Chicago Sunday Tribune Magazine, 9 October 1955, p. 14.

[13] Karmatz, correspondence with the author, 17 May 2005.

[14] “Wilt, Streeter Tell Position,” Chicago Maroon, 12 December 1958, p. 3.

[15] Albert N. Podell, “Censorship on the Campus: The Case of the Chicago Review,” San Francisco Review1, no. 2 (Spring 1959): 75.

[16] Ray quoted in Podell, “Censorship,” p. 72.

[17] Trilling is paraphrased in the editorial to CR 8.3 (1954): 6.

[18] Lolita was published in France in 1955 by Maurice Girodias’s Olympia Press (which would eventually publish Naked Lunch) and then three years later in the US and UK by Penguin/Putnam, resulting in a storm of controversy and bannings from libraries.

[19] Although this is often touted as Naked Lunch’s first appearance in print, it should be noted that a five-page excerpt had appeared in Black Mountain Review7 (Autumn 1957)under the pseudonym William Lee.

[20] New York Times Book Review, 6 April 1958, p. BR8.

[21] New York Times Book Review, 18 May 1958, p. BR2.

[22] The Nation, 2 August 1958, p. 53ff.

[23] William Leonard, “In Chicago, We’re Mostly Unbeat,” Chicago Sunday Tribune Magazine, 9 November 1958, p. G8.

[24] Quoted in Podell, “Censorship,” p. 81.

[25] Chicago Maroon, 12 December 1958, p. 3.

[26] Carroll to Creeley, 3 October 1959. Paul D. Carroll Papers, Box 1, Folder 22, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago.

[27] Rosenthal to Carroll, 7 February 1959. Paul D. Carroll Papers, Box 1, Folder 22.

[28] CR 12.3 (1958): 49.

[29] Creeley mailed this essay to CR on 25 October 1958, the same day that the Daily News decried CR as “Filthy Writing,” precipitating the University’s suppression.

[30] Olson’s correspondence with CR was on letterhead from Black Mountain Review, the magazine edited by Creeley and sponsored by Black Mountain College, where Olson had served as rector for five decisive years until its closing in 1956. A letter from Rosenthal to Olson suggests there was some dissent on staff over publishing Olson’s piece: “I want to accept your book review […] on the basis of style alone, to which the rest of the staff isn’t, let’s say as sensitive as I am” (8 April 1958). CR Records, 15:4.

[31] The Nation, 1 November 1958, p. 311ff.

[32] Time, 21 July 1958, p. 49.

[33] Chicago Daily News, 25 October 1958, p. 1.

[34] Quoted in Gerald E. Brennan, “Naked Censorship: The True Story of the University of Chicago and William S. Burroughs,” Chicago Reader, 29 September 1995, p. 21.

[35] John Boyer, Academic Freedom and the Modern University: The Experience of The University of Chicago(Occasional Papers on Higher Education X, the College of the University of Chicago, 2002), 36–39.

[36] John Boyer, “The ‘Persistence to Keep Everlastingly At It’: Fund Raising and Philanthropy at Chicago in the Twentieth Century,” The University of Chicago Record, 39:1 (3 February 2005), p. 15.

[37] “Autumn 1958 Issue of the Chicago Review,” 30 October 1958. University of Chicago. Office of the President. Records, Box 69, Folder 10, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library. Hereafter cited as President’s Records, [Box #, Folder #].

[38] 3 November 1958. President’s Records, Box 69, Folder 11.

[39] Quoted in Brennan, “Naked Censorship,” 29 September 1995, p. 19.

[40] Quoted in Brennan, “Naked Censorship,” 6 October 1995, p. 5.

[41] Quoted in notes taken during the Student Government committee’s interview with Kimpton, 17 December 1958, p. 5. President’s Records, Box 69, Folder 9.

[42] Memo titled “Chicago Review.” President’s Records, Box 69, Folder 9.

[43] Quoted in Chicago Maroon, 12 December 1958, p. 3.

[44] “Report,” 11.

[45] Quoted in Chicago Maroon, 12 December 1958, p. 3.

[46] Podell, “Censorship,” p. 82.

[47] Quoted in Chicago Maroon, 12 December 1958, p. 8.

[48] Peter Michelson, “On The Purple Sage, Chicago Review, and Big Table,” TriQuarterly 43 (Fall 1978): 356.

[49] The Nation,27 June 1959, p. 580.

[50] “BIG TABLE, INC. v CARL A. SCHROEDER, U.S. Postmaster General” 30 June 1960, p. 10. Box 5: Judge Hoffman, Paul Carroll Papers.

§

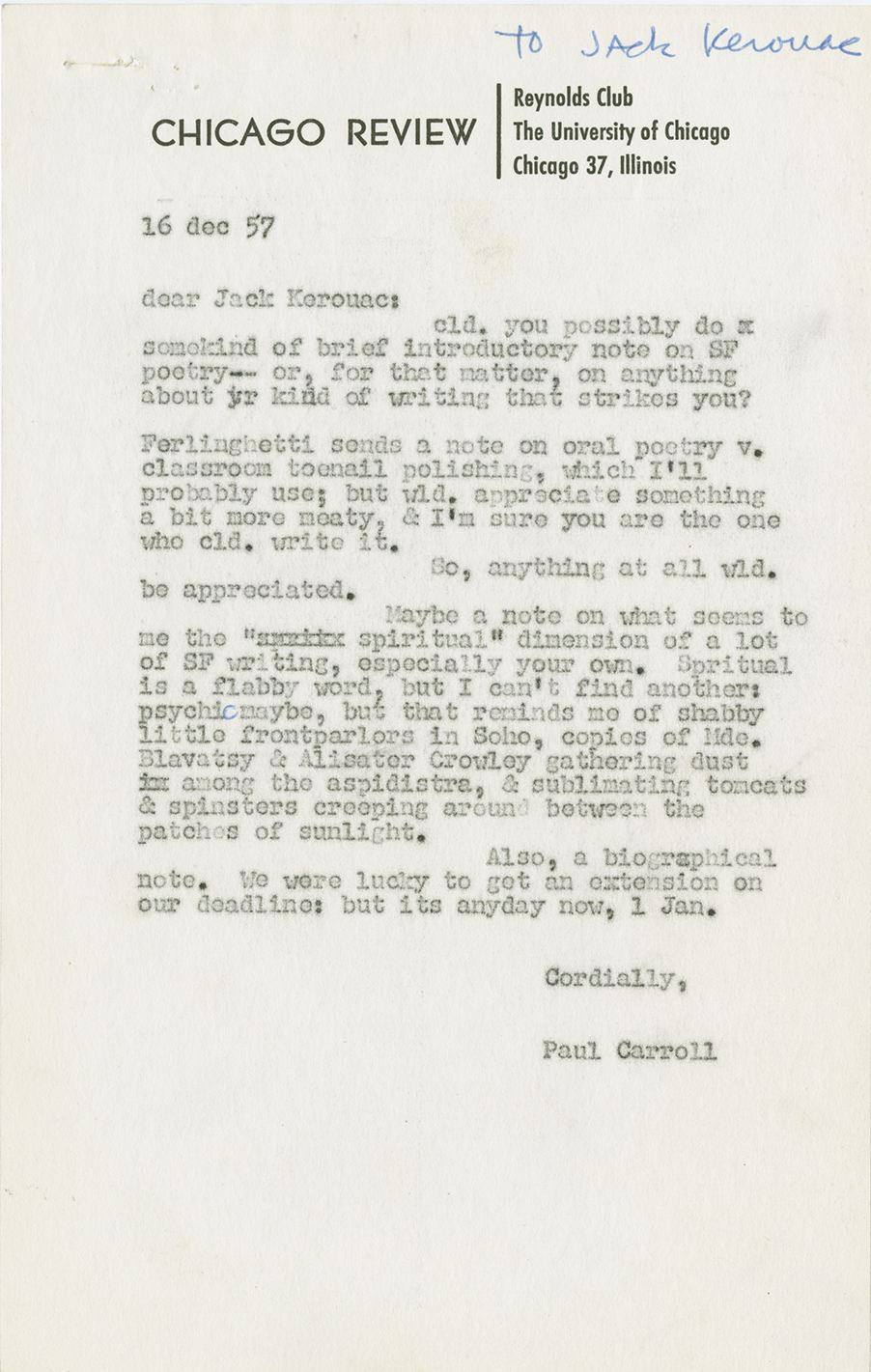

From the CR Archive: Correspondence with the Beats

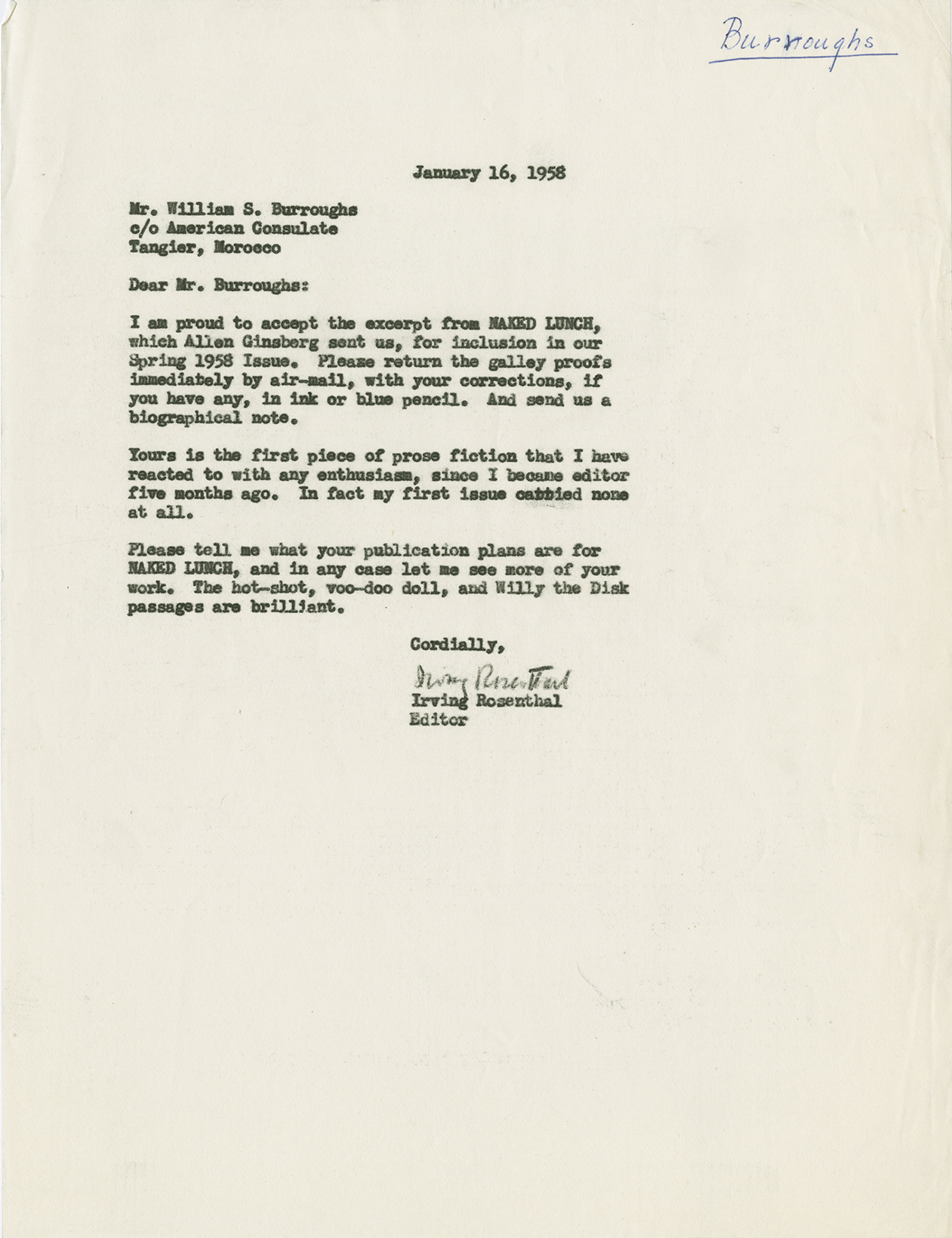

Rosenthal to Burroughs, January 16, 1958. CR Records, 12:2.

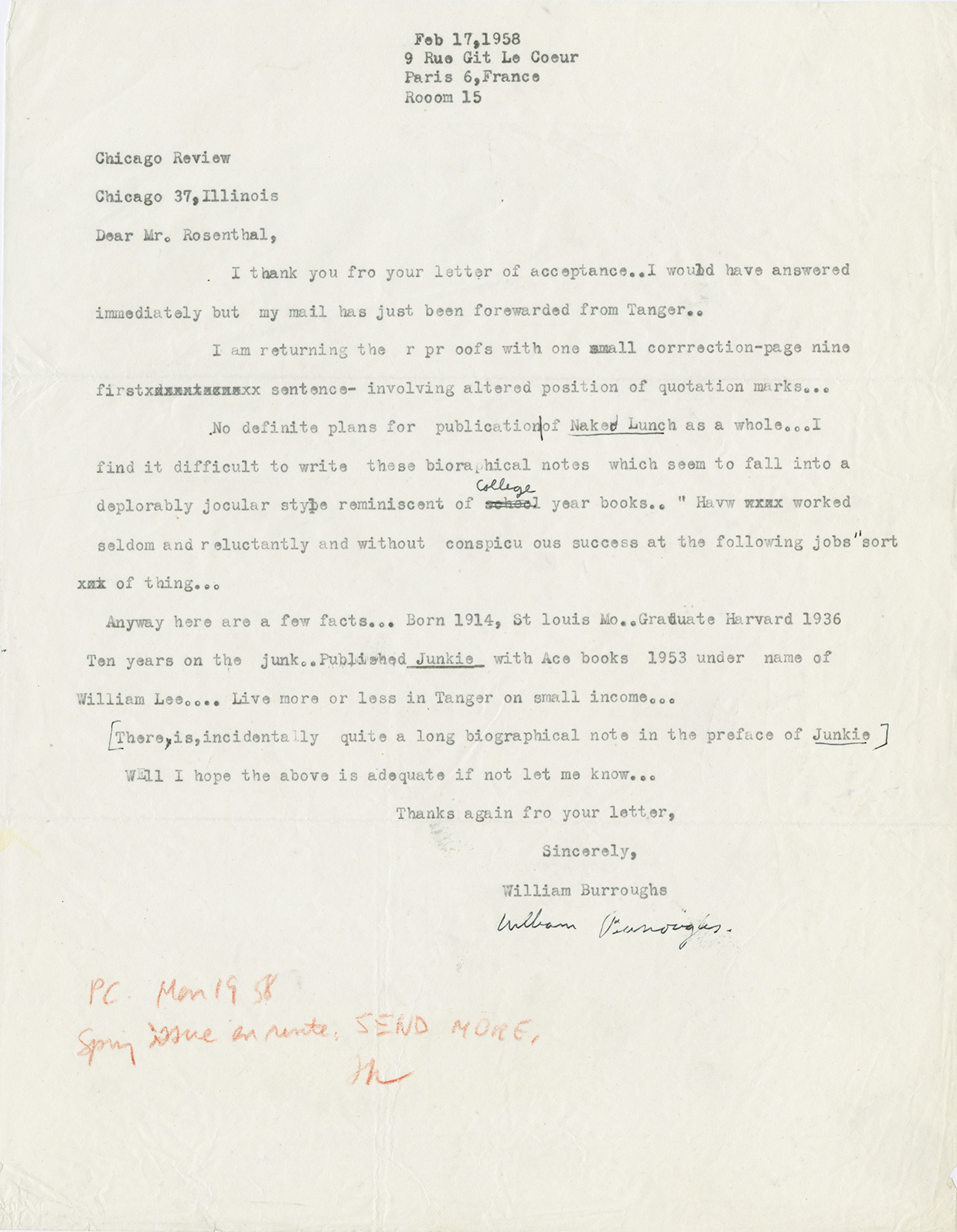

Burroughs to Rosenthal, February 17, 1958. CR Records, 12:2.

Ginsberg to Carroll, December 9, 1957. CR Records, 13:2.

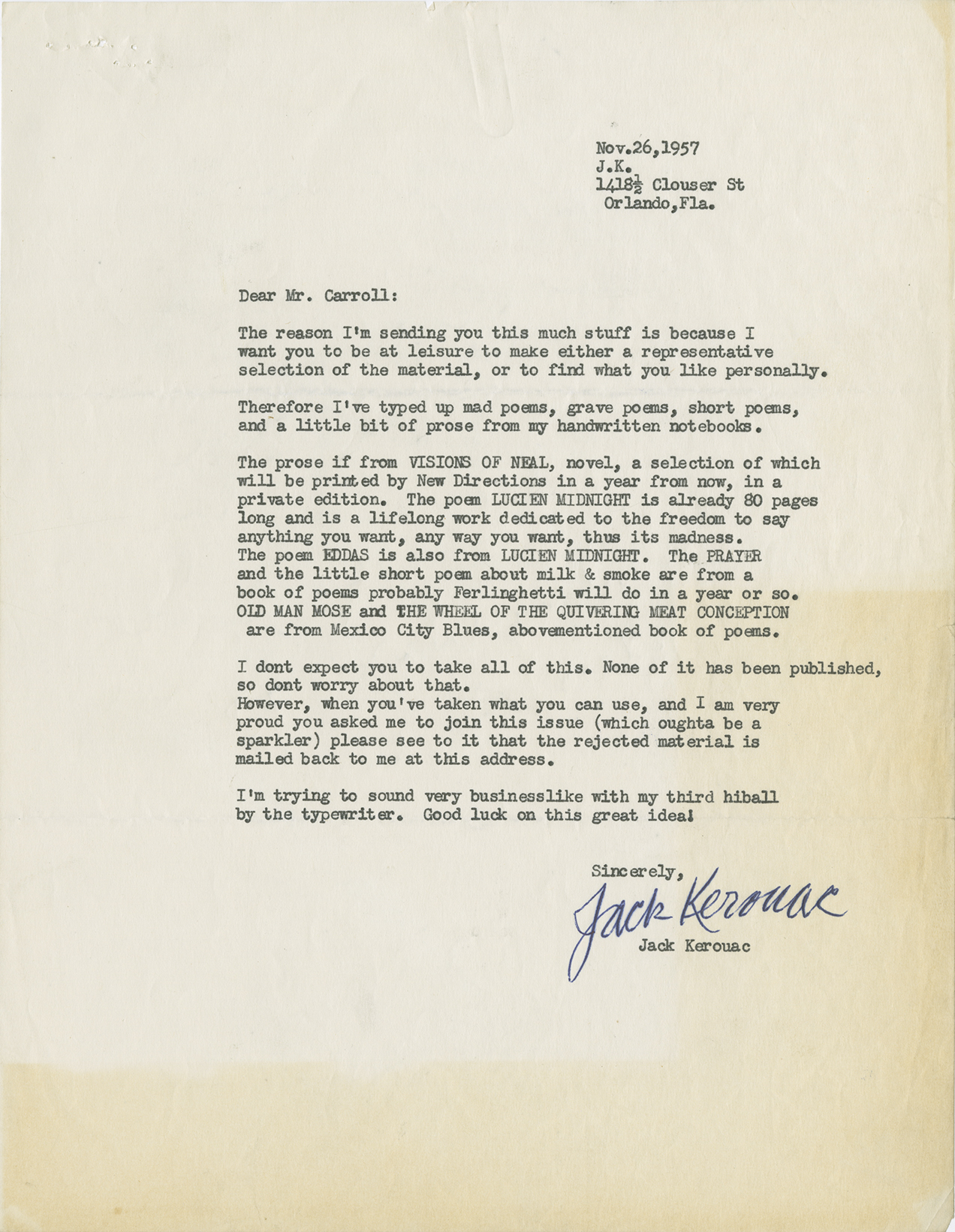

Kerouac to Carroll, November 16, 1957. CR Records, 13:9.

Carroll to Kerouac, December 16, 1957. CR Records, 13:9.

§

Chicago Review Staff Meeting, November 18, 1958

A special meeting of the staff of Chicago Review was held at the Review offices at 4 p.m., November 18, 1958. The meeting was called by editor Irving Rosenthal, who was presiding officer. Mr. Rosenthal explained that the special meeting was necessary in order to resolve certain issues that were of vital concern to the immediate welfare of the magazine.

He informed the staff that it was his understanding that the very existence of the Review was at stake. He explained to the group that the University administration had informed him that if the magazine were to continue it must be under the following conditions:

- The next issue must be of a non-controversial nature.

- The Review must be subject to an annual appraisal by the faculty committee of the magazine.

- In the future, the editor shall check with the faculty commite [sic] before publishing any manuscripts which he thinks might be objectionable.

Mr. Rosenthal said he was told that if the magazine did not comply with these stipulations, it would in all probability be discontinued by the University of Chicago.

He reported to the staff that the University administration had forbidden him to publish in the next issue of Chicago Review any material they considered to be controversial, and that those manuscripts submitted by authors Burroughs, Kerouac and Dahlberg were in this category. He further stated that this was the material he had intended to publish is [sic] the Winter issue of the Review and that he thought very highly of the manuscripts. But as the University was not allowing him to publish these authors, he felt that his only conscience-free choice was to submit his resignation. He stated that he intended to do this in the very near future.

Mr. Rosenthal suggested that one way of approaching the complex situation was to reduce it to two alternative courses of action.

- Refuse to comply with the conditions set forth by the University administration, and in retaliation use all facilities available to force them to withdraw their stipulations. The University might be forced by public opinion to recall its mandate and the manuscripts in question could then be published as planned. This approach could prove to be fatal to the Review if it did not succeed.

- Elect a new editor of the Review who could publish in good conscience a next issue which would be acceptable to the University. This alternative would insure [sic] the continuation of the magazine, although the necessity of publishing one innocuous issue could possibly result in lowering the usual high standard of the Review.

Of those persons qualified to fill the position of editor, only one, Hyung Woong Pak, felt that he could assemble in good faith a next issue that would be of literary merit yet acceptable to the University administration. It was also Mr. Pak’s position that the Review could comply with the stipulations of the administration without lowering its quality and without losing its autonomy.

The staff appeared unanimous in its agreement that the University should not interfere in the affairs of the Review. However there was considerable hesitation in supporting any action that might result in the death of the quarterly.

After much deliberation, the staff members chose the second alternative. By secret ballot and vote of 15 to 2 it was decided that the best course of action was to continue publication and that Hyung Woong Pak should be Chicago Review editor. The ballots were counted by Prof. Joshua Taylor of the Review faculty committee.

The meeting was adjourned by Mr. Rosenthal.

§

from Report of the Special Committee of the Student Government in Re: Chicago Review

CR Records, 5:3.

In the Chicago Daily News of October 25, 1958, critic-columnist Jack Mabley attacked the University of Chicago for permitting the publication under its auspices of the Autumn issue of the Chicago Review. The gist of Mabley’s attack was that the Chicago Review had fallen into the hands of adolescents who were not interested in literature but only in scribbling dirty words on walls. Mabley concluded his article: “I don’t put the blame on the juveniles who wrote and edited the stuff, because they’re immature and irresponsible. But the University of Chicago publishes the magazine. The trustees should take a long hard look at what is being circulated under their sponsorship.”

Several weeks later, on November 29, the Chicago Maroon reported the resignation of the Review’s editor-in-chief, Irving Rosenthal, ascribing his resignation to personal reasons. The article reported the election of a new editor-in-chief, Hyung Woong Pak, and the selection of a completely new editorial board. In the article, Pak stated that the scheduled Winter issue of the Review would not appear due to a missed deadline at the University Press.

At the December 2 meeting of the Student Government of the University the question of the Review was raised. It was suggested that the old editorial board actually resigned in protest to a demand by the University Administration that writing by certain named authors be excluded from the Winter issue. It was further alleged that the missed deadline was not the principle [sic] reason for the failure of the Winter issue to appear.

Student Government formed a special committee to investigate these allegations. The committee consisted of Diana Eagon, Law; Jack Eagon, Physical Science; Phillp Epstein (Chairman), College; Leon Kass (non-government member), Medicine; Jack Michaelsen, Business; Michael Padnos, Law; Gary Stoll (non-government member) Law.

In making this investigation, the committee sought to answer three questions:

- What actions, if any, did the University take concerning the publication of the Winter issue of the Chicago Review?

- What were the reasons for these actions ?

- What fair evaluation can be made of the actions and their motivations ?

It is the conclusion of this committee that there was action taken by the University Administration. The resignation of the editors and the failure of the Winter issue to appear were both due to pressure imposed by the Administration of the editors. The University threatened to prevent publication of the Review if the editors attempted to print manuscripts which might cause further adverse press comment of the University. The committee further concludes that the principal reason the University imposed pressure on the editors was that the University itself was under pressure from persons financially interested in the University to prevent the appearance of another such issue.

Before evaluating these actions and motivations, it is necessary to review all the pertinent facts which led this committee to the above conclusions. These facts were gathered in a series of interviews with all persons who were concerned with the Review: the old and new editors, old and new members of the editorial board, University Press personnel, the Comptroller of the University, members of the Faculty Advisory Board of the Review, Deans Wilt of the Humanities and Streeter of the College (whose budgets supplied the University’s subsidy to the Review), and Chancellor Kimpton.

- WHAT ACTION WAS TAKEN?

Determination of why the editors of the Review resigned and why the Winter issue did not appear were the first tasks which faces the committee. Interviews with Irving Rosenthal the editor-in-chief who had resigned, and with other editors and staff members supplied the information.

The resignation resulted from a demand on the part of the “Administration” that the Winter issue of the Review be “innocuous”, i.e., free of obscene words. Specifically, Dean Wilt had informed Rosenthal that material by Kerouac, Dahlberg and Burroughs which had already been accepted for publication in the Winter issue could not appear. Rosenthal told Wilt and Streeter that he personally could not comply with these conditions, but that he would consult the staff of the Review. On November 18, Rosenthal outlined these conditions to his staff and asked if anyone could, in good conscience, accept the editorship under these circumstances. Only Hyung Woong Pak felt that he could comply. Rosenthal then resigned, and Pak was thereupon elected editor-in-chief. The resignations of the other editors followed. The planned Winter issue abandoned, a substitute Winter issue did not appear because Pak and his new staff found it physically impossible to select and edit a completely new set of manuscripts..

To establish the actual measures taken by the University, the committee undertook an inquiry into a series of meetings at which Dean Wilt communicated the above conditions to Rosenthal. These meetings, held approximately every second day, ran from November 3 through November 17. Dean Streeter was also present at the meetings on November 17. The following account, given by Rosenthal, was later and separately substantiated by Wilt and Streeter.

At one of the first meetings, Will told Rosenthal that unless some changes were made in the proposed content of the Winter issue, he didn’t know “but what the money might be cut off from the Review.” At the next meeting Wilt said that “the financial authorities of the University”[2] had definitely assured him that unless the Winter issue was “completely innocuous” the University would withdraw its financial support from the magazine. Although “completely innocuous” was Wilt’s phrase to Rosenthal, and not necessarily used by the financial authorities” to Wilt, Wilt made it clear that the financial authorities’ concern was over the “gamy” writing which had appeared in the Autumn issue, and which they feared Rosenthal planned to repeat in the Winter issue. There was some discussion of asterisking out the four-letter-words in the manuscripts, but this idea was rejected by both Wilt and Rosenthal and “puerile”.

At the subsequent meeting Wilt told Rosenthal that Burroughs, Kerouac, and the San Francisco poets generally could not appear in the Winter issue. However, he expressed his belief that all forbidden manuscripts which had been accepted could appear, singly, in later issues. Wilt offered to inquire whether a not could appear in the revised Winter issue, announcing that the manuscripts in question had been accepted but could not appear at this time.

Not until a later meeting was Rosenthal told that Dahlberg’s manuscript also could not appear. However, Wilt stated that he had obtained permission for the inclusion of the note. It was made clear to the committee, but perhaps not to Rosenthal, that the “financial authorities” did not object to these writers specifically. Rather they objected to their use—or anyone else’s use—of obscene words in (at least) the Winter issue.

On November 17, at the last meeting held between Rosenthal and the Deans, the following possibilities were outlined:

- Rosenthal could attempt the publication of the planned Winter issue, most likely incurring the withdrawal of the (usual) financial support of the University.

- Rosenthal could change the proposed issue to meet the prescribed conditions.

- Rosenthal could resign, leaving the decision to the rest of the staff and/or his successor.

Wilt and Streeter advised the second course, and strongly urged Rosenthal not to take the first course, in the interest of preserving the magazine. Rosenthal said that for both moral and practical reasons, he could not edit a new “innocuous” issue for the Winter of 1959. He did not agree to present the alternative to his staff, with the result as has been reported: Pak was elected editor, and all the other editors resigned in protest to the Administration’s actions.

From the information given this committee by Dean Wilt, this committee has concluded that the University deprived the editors of the freedom of independent editorial judgement traditionally enjoyed by the Chicago Review; further, that the editors resigned because they could not, in good conscience, accept dictation from the University as to the content of the magazine.

III. EVALUATION AND CONCLUSION

In what way were the influences that were brought to bear upon the student editors wrong, if indeed they were wrong ? In this final analysis, has the University failed to serve its own best interests by suppressing the opinions of these students? It was suggested early in the course of our investigation that the following three concepts should be called relevant:

- Freedom of the Press: that guarantee of law which insures that no interference shall be made with the publisher in his right to publish what material he chooses. The University is the owner and publisher of the Chicago Review; therefore, the University was certainly within all legal rights in appointing whom it chose as editor, and publishing what it chose in the magazine. For this reason, the committee feels that this issue is not relevant to the suppression of the Review.

- Academic Freedom: that freedom of action which the University guarantees its faculty, as faculty members, in their scholarly pursuits and private lives. This freedom is held to extend, perhaps to a more limited extent, to the student body. The committee feels that this concept is partly relevant to the case of the Review. The editors had indeed enjoyed a tradition of the non-interference with their literary judgments, and it is arguable that this tradition lies within the scope of academic freedom. However, it may be argued that literary quality is a criterion upon which the student editors, as students, should be judged. Thus the University might feel that it had a duty to evaluate the work of the students even to the point of forbidding publication in extreme cases. Nevertheless, those members of the Humanities and College Faculties who comprise the Faculty Board—not the “financial authorities” in the Administration—should be the ones to make such decisions. It may be recalled that the Faculty Board was in favor of permitting the publication of the Winter issue as originally planned.

- Intellectual Atmosphere: this concept is at once the most difficult to define and the most relevant in the view of the committee. We believe that the Administration and Faculty have an obligation, as our teachers, not only to permit publication of student work, but to insist vehemently on the independence of student judgments from outside intimidation and threats. In working to encourage the intellectual growth of its students the University must provide the atmosphere for new ideas to be tried, new views to be expounded. It is this intellectual atmosphere which we feel is most seriously challenged by the Chancellor’s capitulation to the whim of the local columnist.

It is especially when new views run counter to those of the society that the University should act most vigorously to protect its members from the pressures to conform. This is not to say that the students should ignore the pressures of society, but except as these pressures act on the very consciences of the students themselves, they ought to act at all.

What is the purpose of supporting a student-run publication if not to give the students a chance to exercise their literary judgements and abilities? If the magazine is to reflect the “literary taste and judgment of the Humanities Faculty” then it should be a Humanities Faculty publication. If the Review is properly to be called a student publication then it should reflect the judgement of the Humanities Faculty only to the extent that the student editors themselves feel that judgement to be valid.

In our University there is one man who has the ultimate responsibility for protecting the students’ interests: Chancellor Kimpton. It is to him that we must look for reassurance that we have not actually lost the atmosphere of freedom that should surround our activities. The committee feels that Chancellor Kimpton should in word and deed reaffirm the principle that the University will encourage and protect its members in their exercise of the right of free intellectual inquiry and expression.

Notes: